Hungarian Romani Youth Empowerment through Sport – Miskolc, Hungary

Sarath Pillai is a Ralph W. Nicholas Fellow and international student from India studying History in the University of Chicago Social Sciences Division. He will use the grant for his project Hungarian Romani Youth Empowerment through Sport. This project will support an institutional upgrade of the Dr. Ambedkar High School in Miskolc, Hungary, amplifying its mission to foster Romani and non-Romani youth social integration and cultural exchange. This unique institution, founded in 2007, enrolls approximately 90 students each year, primarily of Romani ethnicity, from across northeastern Hungary and eastern Slovakia, in communities where high school completion is often lower than 1%. Funds from this grant will support the development of recreation spaces and sports facilities of the school and its affiliated residential hall, the Martin Luther King Dorm. During a four-week development phase, Sarath will work with the local NGO KultúrAktív to run sessions with Ambedkar teachers to discuss how these facilities can be incorporated into curricular and extracurricular activities. This project will strengthen the school’s position as a dynamic, transnational site of Romani youth empowerment and interethnic exchange for years to come.

Sarath Pillai is a Ralph W. Nicholas Fellow and international student from India studying History in the University of Chicago Social Sciences Division. He will use the grant for his project Hungarian Romani Youth Empowerment through Sport. This project will support an institutional upgrade of the Dr. Ambedkar High School in Miskolc, Hungary, amplifying its mission to foster Romani and non-Romani youth social integration and cultural exchange. This unique institution, founded in 2007, enrolls approximately 90 students each year, primarily of Romani ethnicity, from across northeastern Hungary and eastern Slovakia, in communities where high school completion is often lower than 1%. Funds from this grant will support the development of recreation spaces and sports facilities of the school and its affiliated residential hall, the Martin Luther King Dorm. During a four-week development phase, Sarath will work with the local NGO KultúrAktív to run sessions with Ambedkar teachers to discuss how these facilities can be incorporated into curricular and extracurricular activities. This project will strengthen the school’s position as a dynamic, transnational site of Romani youth empowerment and interethnic exchange for years to come.

April 29, 2021

I am delighted to start this blog. I will use this blog to make periodic updates about my Davis project, Hungarian Romani Youth Empowerment through Sport, which will be implemented at the Dr. Ambedkar High School in Miskolc, Hungary, this summer.

Just a brief note about me: I am Sarath Pillai, a PhD Candidate in the History Department at the University of Chicago. I am a one-time resident of International House and a five-time awardee of the Ralph Nicholas Fellowship. I was born and raised in Kerala, India, and did most of my higher studies in Delhi before coming to the US in 2013. I hold degrees in history, law, and archival studies. My PhD thesis examines the rise and fall of federalist ideas in interwar and postwar South Asia, in which constitutionalists like B. R. Ambedkar played a crucial role.

The Ambedkar School is the premier educational institution for underprivileged Romani youth in Hungary, helping them finish high school and make them qualified for higher education or gainful employment. The main thrust of our project will be the overall development of school facilities. We have identified four important areas: redesign and renovation of school spaces, building a new volleyball court, a basketball court, and a community garden.

As we begin this project, I want to thank all the partners and collaborators who helped me make a successful Davis grant application. First, Roy Kimmey, PhD Candidate in History at UChicago and a student of Hungarian and Romani history, has been working on this project as much as I am. While it is too early to thank him, I want to put on record all the advice and help he gave me while I prepared the application and thank him for facilitating conversations with people on the ground. Second, Nóra Tyeklár, our point person at the school and the Director of Martin Luther King Dormitory, has been unceasing in her cooperation and enthusiasm. She helped us identify the priorities for the school and propose a project that will address their immediate needs. We are also extremely delighted to have the support of the founders of the school, János Orsós and Tibor Derdák as well as Roland Imre, financial officer of the school. All of them have been extremely forthcoming with the implementation of this project. KulturAktív, an organization with proven expertise in building spaces that are interactive and sensitive to the needs of students, had collaborated with us at the conception of this project and will continue to work with us to implement this project. We are grateful for their ongoing support and investment in this project.

Last but not least, Denise Jorgens, Deb Jasinski, and Hannah Barton have been extremely helpful in not only preparing the application, but also for offering to work with us closely in the coming weeks to complete this project and for offering their unstinted support, both material and non-material.

In the next blog, we will give you more details about the school, its mission, and our intended project! In the meantime, enjoy these pictures and videos that Nora and Tibor sent me on the occasion of Ambedkar Jayanthi (April 14 marks the birthday of B. R. Ambedkar) celebrations at the school held in conjunction with the Indian Embassy in Budapest.

Stay tuned for more!

June 21, 2021

The last two months have been full of planning meetings and collaborations with our project partners in Hungary. One of our first activities in April was to hold a Zoom meeting with the founders of the Dr. Ámbédkar School, János Orsós and Tibor Derdák, along with Nóra Tyeklár, director of the dormitory, and Roland Imre, the school’s financial officer. We discussed the unique nature of the school and the transformative impact they would like to see through the Davis Projects for Peace grant.

The last two months have been full of planning meetings and collaborations with our project partners in Hungary. One of our first activities in April was to hold a Zoom meeting with the founders of the Dr. Ámbédkar School, János Orsós and Tibor Derdák, along with Nóra Tyeklár, director of the dormitory, and Roland Imre, the school’s financial officer. We discussed the unique nature of the school and the transformative impact they would like to see through the Davis Projects for Peace grant.

The school staff stressed the importance of personal connections as an opportunity for students to learn about the world outside of their immediate communities. Many students at the Dr. Ámbédkar School are of Romani ethnicity and come from socially marginalized and economically disadvantaged communities. In Hungary, as well as much of east central Europe, only a small percentage of Romani youth complete more than eight years of schooling. In Borsod, the county in which the Dr. Ambedkar School is located, ranks among the most economically disadvantaged regions in the European Union and school dropout rates are among the highest nationally.

To address these needs, János Orsós and Tibor Derdák founded the Dr. Ámbédkar School in 2007 in Sajókaza, Hungary. Its namesake is Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar; it is the only high school in Europe founded in Ambedkar’s name. Today, Ambedkar is remembered for his steadfast quest for social justice for the oppressed castes (Dalits) in India. A Dalit himself educated at Columbia University and the London School of Economics, he led the Dalit movement in India until his death, in the process authoring the constitution of free India in 1950.

Ambedkar inspires the school in its mission to empower Romani youth. Over the past thirteen years, first in Sajókaza and today in its expanded campus in Miskolc, 113 adult students have completed primary school education and 114 students have taken a graduation exam in one or more subjects. In 2018, the school expanded its outreach to students in neighboring villages in northeastern Hungary and eastern Slovakia with the opening of the Martin Luther King Jr. Dormitory.

The Davis Project will help carry the school into its next phase of expansion and development. Infrastructural improvements to the schoolyards, including sports fields and community gardens, will provide spaces for the students to engage in team building exercises and help them form stronger connections with their environment. Additionally, the school’s leadership team spoke enthusiastically about the opportunities for lasting and deep institutional and personal ties between the students at the school and the wider University of Chicago International House community. As such, we are striving to build social and personal ties with the school alongside these critically important infrastructural projects.

This project has brought together a wide network of organizations across Hungary. One key partner is the LADDER (Laboratory with Kids for Democratic School Environments) Living Lab, which itself unites the work of the Institute of Landscape Architecture, Urban Planning & Garden Art of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences and the KultúrAktív Association, which contributes a specialization in built environment education. Through trainings, informational meetings, and group discussions, we have already learned a great deal from the LADDER team, who have introduced us to their philosophy and practice of student- and community-centered urban planning and environmental education. Thus, the Davis Project has opened yet another avenue for transnational, cross-institutional collaboration.

Of utmost importance to all of us is that students feel engaged and involved in all stages of the project’s development. In order to facilitate discussions with students and teachers at the school and solicit their input on the development of the schoolyard, we spoke with a team of representatives from the LADDER Living Lab, including Anita Reith, a PhD student and lecturer at the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences (as well as freelance landscape architect) and Anna Szilágyi-Nagy, president of KultúrAktív. A few weeks ago, the team traveled to Miskolc and held two roundtables with the school community to identify challenges at the school and to devise a common vision on how to address these.

In the next blog posts, we have invited Anita to introduce our institutional partners in Hungary, to describe the community-centered, democratic approach to project development the LADDER Living Lab team has devised, and to describe the key findings of the workshops. These ideas drive the project today as it moves into the construction phase.

Thank you to Roy Kimmey for his continuing assistance and for his help in preparing this post!

July 12, 2021

Introducing our Project Partners

Our organizational partners at the LADDER (Laboratory with Kids for Democratic School Environments) Living Lab held two workshops with the students, faculty, and staff of the Dr. Ámbédkar School in Miskolc, Hungary. At these workshops, the LADDER Living Lab team facilitated community conversations to help identify the school’s most pressing concerns and to generate ideas of how to address them. In this and the following two blog posts, we’ll introduce the LADDER Living Lab and the organizational partners that carried out these workshops. These workshops provided the basis for the plans we are implementing in the project’s current construction phase, funded by the Davis Projects for Peace grant.

We would like to thank the LADDER Living Lab team and the Dr. Ámbédkar School community for their ongoing work in generating a common vision for the development of the school grounds!

An Introduction to the LADDER Living Lab and LED2LEAP

The LADDER Living Lab supports school communities to collaboratively shape the outdoors. Participation is key to creating more efficient and safer environments. It also provides students experience in practicing democracy and teaches youth how they can discover, observe, understand, and actively shape the environment and landscape they live in.

The LADDER Living Lab is led by the Institute of Landscape Architecture, Urban Planning & Garden Art of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Its work is carried out in partnership with the KultúrAktív Association, bringing a specialization in built environment education. This collaboration was formed under the umbrella of the LED2LEAP (Landscape Education for Democracy towards Learning, Education, Agency and Partnership) Erasmus+ project, an international initiative that identifies opportunities for and promotes landscape democracy. Six months ago, the Dr. Ámbédkar School in Miskolc, Hungary joined the LADDER team. Since then, the team has participated in many organizational meetings. However, due to COVID-19, these were conducted mostly online or remotely. In the spring semester of the 2020/2021 academic year, university students in landscape architecture began analyzing and mapping the school community and the environment in which they currently operate. These university students prepared interviews and remote site visits to understand local challenges and opportunities related to the local environment. In the end of May, the LADDER team finally had the opportunity to visit the school community in person. We held two workshops with the school community – including students, teachers, and staff – to set a common vision and goals for the development of the schoolyard and dormitory garden.

Identifying a Common Challenge: Workshop #1 at the Dr. Ámbédkar School

During this first workshop at the Dr. Ámbédkar School, we focused on identifying a common challenge. Before setting a common vision and specific goals, it is important to agree on a common challenge that the community feels related to. Therefore, we prepared in advance – in consultation with the leaders at the school – six different scenarios that reflect the school’s challenges. While these scenarios differ, they overlap in many ways.

1. An Open Schoolyard:

What happens if we open the gates of the schoolyard? Can a schoolyard both welcome students and engage the local community (friends, family, etc.)? Can it act as a social hub?

2. An Outdoor Schoolyard:

Learning outside can be fun. But how can we provide an environment that is comfortable and conducive to outdoor teaching? What can we learn from or in nature? How can we create places for learning in groups and alone?

3. An Active Schoolyard:

What kind of active functions can we have in the schoolyard? How can we engage everyone from the school community and offer outdoor activities for all? How can we keep the schoolyard active all year long?

4. The Schoolyard as a Home:

How can we create a safer, more comfortable environment that is not only cozy, but feels like home? How can small things (colors, flowers, benches, artwork, etc.) make a big impact on the schoolyard’s atmosphere?

5. Life after School:

What is the best use for the schoolyard during breaks? How can we use the schoolyard during afternoons and weekends? What happens during the summer break?

6. Redesigning the Schoolyard:

How can we use already-existing structures that are not originally designed for educational use? For example, what could we do with the garages? How can we turn the disadvantages of the space into advantages?

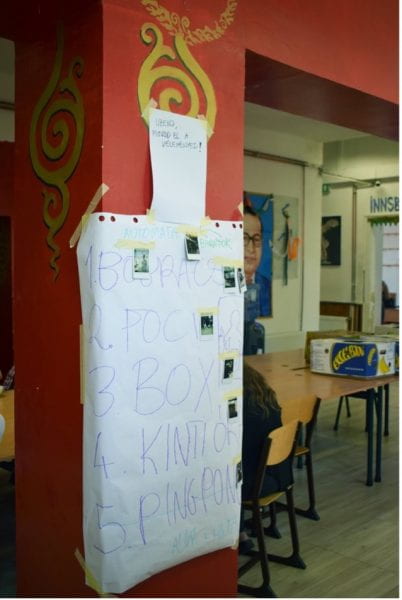

In an opening exercise, we asked participants to choose the scenario they felt most connected to. We designated six spots, each of which corresponded to one of the scenarios. Participants then had to go to the spot they choose. After a first round of selection, we had a short discussion and erased the three spots with the fewest votes. Participants gathered again and we held a second round. While in the first round, participants visited a wider range of scenarios (only ‘Life after School’ received 0 votes), during the second round a wide majority of the participants – 13 out of 20 – selected ‘An Active Schoolyard.’ The other seven participants selected ‘Redesigning the Schoolyard’ (five) and ‘The Schoolyard as a Home’ (two). The aim of this task was to find out what aspects, questions, and challenges of the school’s environment are important to the students and teachers.

After selecting a common challenge, we asked the participants to set goals collaboratively to address this challenge. To this end, we used a method called the ‘Nominal Group Technique’ that is designed to facilitate democratic decision-making processes. First, we asked participants to write two goals individually that they thought important.

After that, we had a sharing round, where everybody had to explain these two goals to the group and then add them to our common idea wall. At this time, only clarification questions were allowed by the others. Once we had all the individual goals up on the wall, we started to create clusters of similar goals.

After organizing the goals, we asked the participants to vote for their favorites. Everyone had five votes and there was no restriction on how they could use these votes. Participants could use their five votes for one goal, for five different goals, etc., and marked their choices using stickers. After this voting session, we reviewed the results and identified four themes that received the most votes:

Theme 1: Food Goals (a vending machine, planting fruit trees and a vegetable garden, creating an outdoor dining area, caring for livestock)

Theme 2: Outdoor Exercise and Play Goals (outdoor gym, darts, foosball, ping-pong)

Theme 3: Group Sports Goals (football, basketball, badminton)

Theme 4: A Sculpture of Me

In addition to the themes mentioned above, other goals included more school programming, an outdoor library, a designated smoking area, outdoor classrooms, solar-powered lighting, and a swing.

Theme 4 (A Sculpture of Me) began as a joke of one student, who suggested the goal of putting up a sculpture of himself in the schoolyard. With his friends, they together put up many votes for this goal; consequently, we had to take this goal into consideration as we did not want to intervene and take it down. After the voting session, we formed four groups from the participants. Each group worked on the four themes in parallel and developed a more concrete vision for what these goals could mean and what actions could help fulfill them. They worked on big boards and could select from previews that we printed for them in advance.

As the students who voted for Theme 4 (A Sculpture of Me) declined to work further on this topic, the other participants who got this topic were less than enthusiastic about the idea. They changed the theme to ‘more school programs,’ which turned out to be a very good topic, based on the feedback we received later.

July 19, 2021

Relating Proposals to the Real Space: Workshop #2 at the Dr. Ámbédkar School

During the second workshop at the Dr. Ámbédkar School in Miskolc, Hungary, it was important to separate the goals and visions for the schoolyard and the dormitory’s garden discussed during the first workshop and relate these proposed activities to the real space. As a warm-up exercise, we created a list of functions and activities that were mentioned in the first workshop and asked participants to designate where they would like to do each activity. To facilitate this exercise, we provided four specific spaces, positioned in four different corners, in which each activity could take place: the schoolyard, the dormitory’s garden, somewhere else, and nowhere. For each activity, participants had to move to the corner that represented where they wanted the activity to take place. This exercise helped us to separate different activities and functions according to the institution’s two gardens. Additionally, it was a great exercise for the students and teachers to revisit and evaluate what they mentioned during the first meeting. Thus, the exercise not only refreshed the participants’ memories, but also helped them start to imagine participating in the proposed activities and functions.

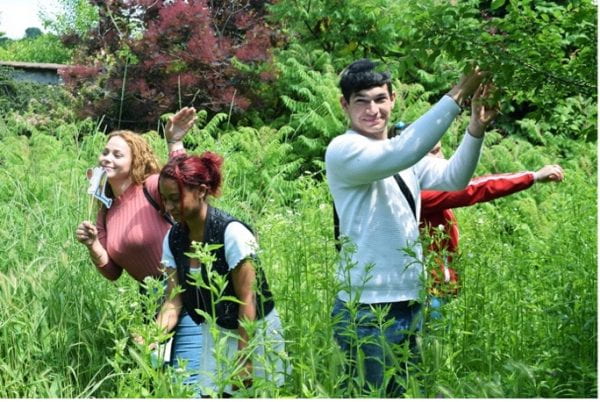

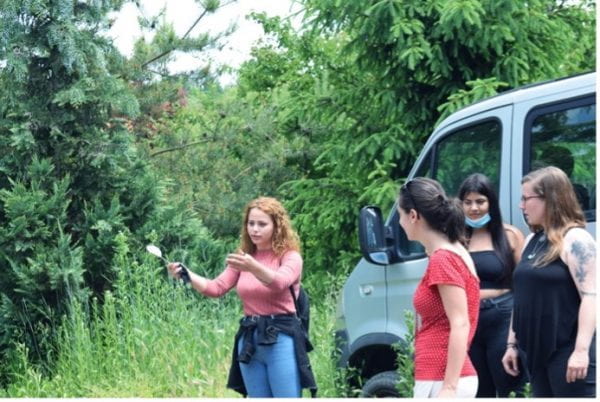

After that, we separated the participants into two groups to work in parallel on the schoolyard and the dormitory’s garden. Both groups went to the actual sites where they had to imagine the proposed functions and find the best place to carry them out.

After some discussion, they were asked to create a human sculpture that represented the activity or the function.

With Polaroid instant cameras they took pictures of themselves, aided by small props related to these activities and functions that we prepared in advance. By acting as if the proposed activities and functions were already in place and ready to use, the participants engaged in meaningful conversations among themselves and discovered some useful details about the materials, directions, and scales of the future objects.

When the two groups gathered again, they shared their findings with each other.

We put their Polaroid pictures up on a board we affixed to a wall of the school; this board could also be used to collect additional feedback following the second workshop from the wider school community. We believe that this exercise was not only useful for the project team to relate the future function to the space, but also for the school community to imagine and experience their visions through these prototypes.

Thank you to Anita Reith, PhD Student and Lecturer, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences (Landscape Faculty) for your contribution to this blog!